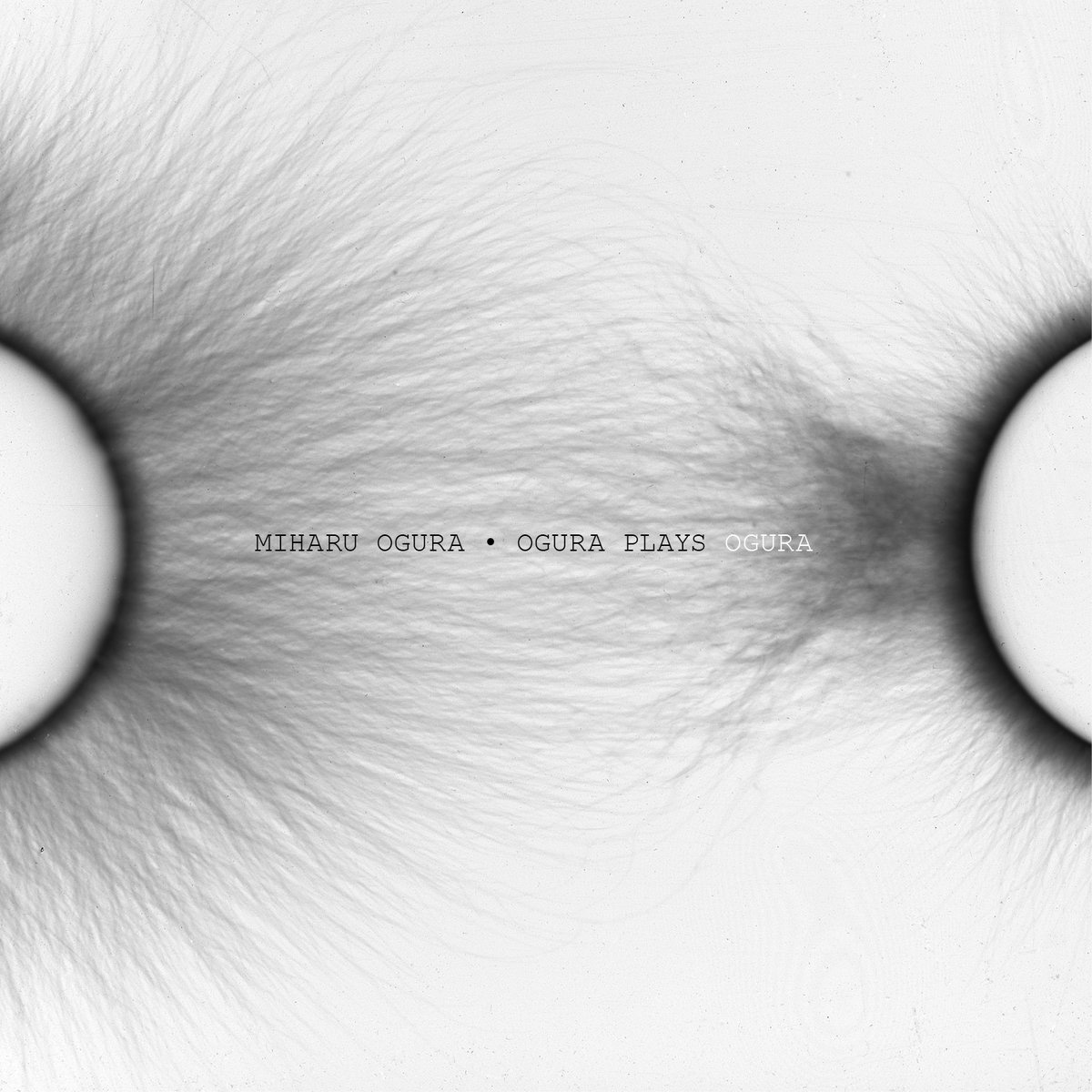

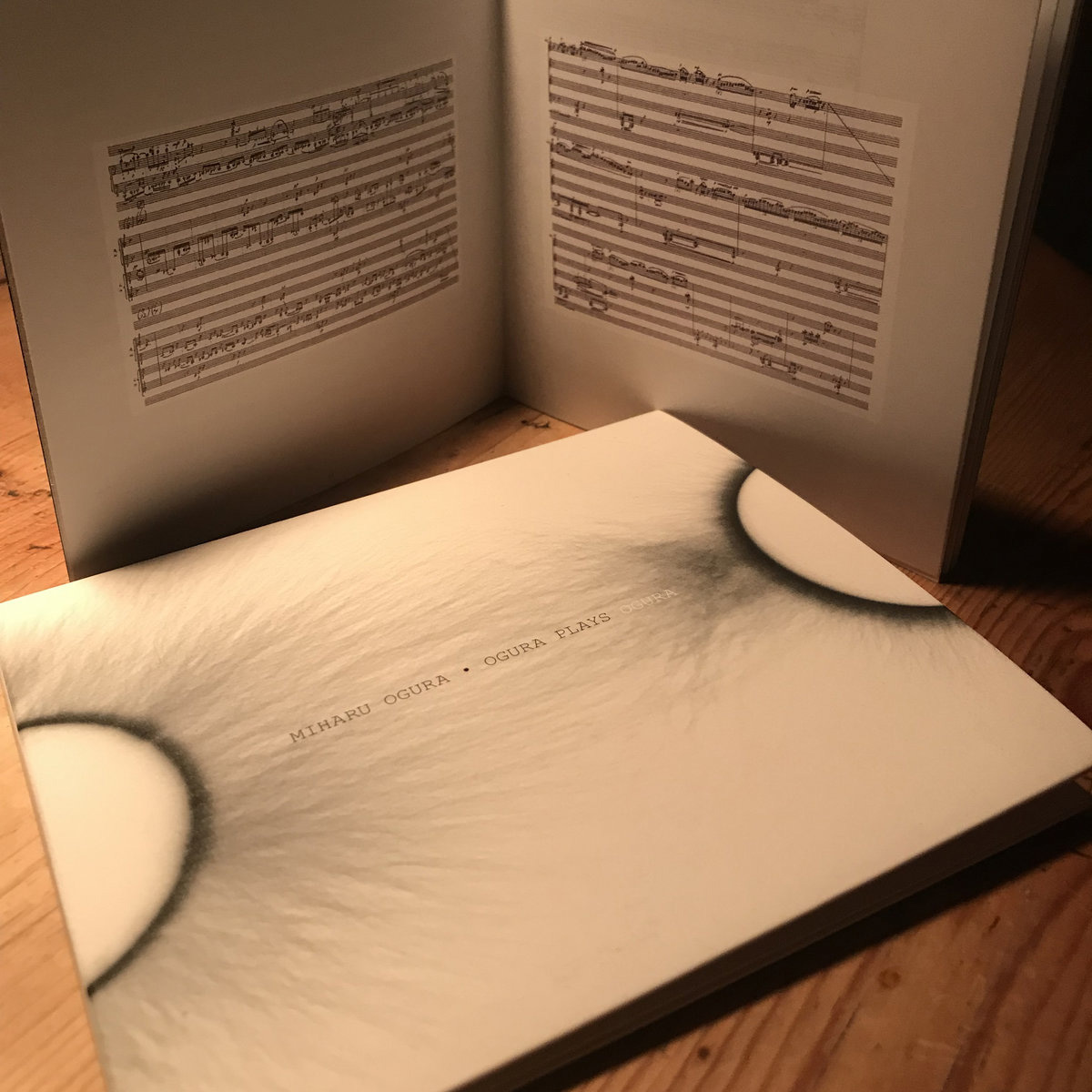

Artist: Miharu Ogura

Title: Ogura Plays Ogura

Label: Thanatosis Production

Cat nr: THT30

Format: CD

Style: Classical/Contemporary Classical/Piano

Tracklist:

| 1 | Pas | |

| 2 | Labyrinthe | |

| 3 | …Zwischen… | |

| 4 | Sillage De Lignes | |

| 5 | Nijimi |

- Recorded At – Fazioli Piano Salon

- Recorded At – Studio Epidemin

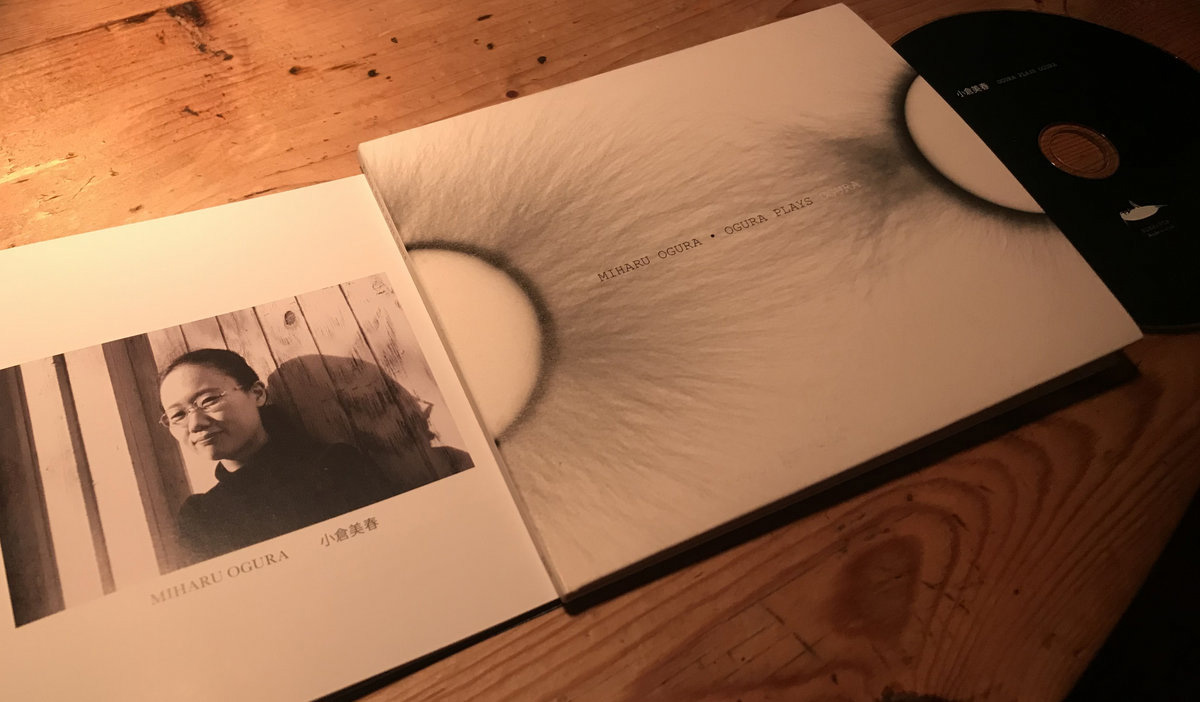

Digi-sleeve.

All music composed and performed by Miharu Ogura. Recorded on a Fazioli F212 Grand Piano, April 27, 2023, at Studio Epidemin, Göteborg. Recording, mixing and master ing by Johannes Lundberg. Liner notes by Jonas Olsson. Design by Michell Zethson & Sara Lundén. Sleeve photos: Helmer Bäckströms arkiv / Tekniska museet. Artist photos by Ingeborg Zackariassen. Executive production by Alex Zethson.

Following her critically acclaimed Stockhausen-album (Thanatosis 2023), Japanese pianist Miharu Ogura (b. 1996 in Tokyo, Japan) now displays her skills not only at the piano but also as a composer. This latest musical endeavor unveils five intricately crafted compositions, each a testament to Ogura’s musical brilliance, delivered with her signature delicacy, precision, and soulfulness. In the international press, Ogura’s remarkable and prize-awarded playing have drawn comparisons to David Tudor and Aloys Kontarsky, and this new set of original, staggering pieces is a lucid account of Ogura’s vast musical imagination. The album was recorded on a Fazioli F212 Grand Piano, at Studio Epidemin in Gothenburg, Sweden. It’s published digitally and on a limited CD edition coming in a digi-sleeve and including a booklet with insightful liner notes by fellow pianist Jonas Olsson, who have also performed several of Ogura’s work.

BIO. Pianist and composer Miharu Ogura (b. 1996 in Tokyo, Japan) is currently based in Frankfurt, Germany. She has won several awards, notably the “André Chevillon – Yvonne Bonnaud” prize at the Orléans International Piano Competition in 2018 which launched her international career. She has since toured across Europe with performances at Darmstädt Ferienkurse, ManiFeste, Klangspuren Schwaz, Festival Mixtur, and Stockholm’s Monopiano Festival. Her debut album, “Ogura Plays Stockhausen”, featuring her live performance of Stockhausen’s Klavierstücke I-XI, was published in February 2023 on Thanatosis produktion and

has received great reviews, for example in UK, peer-reviewed journal TEMPO. As a composer, her works have been performed by ensembles and musicians such as Trio Estatico, Zöllner-Roche Duo, Francesco Tristano and Jonas Olsson. She has received commissions from Radio France and Biennale di Venezia. In November 2023 she won second prize at the 2023 Olivier Messiaen International Competition, plus the prize for best Messiaen interpretation.

NOTES on Ogura Plays Ogura, by Jonas Olsson

Historically, the figure of the composer-performer has often been a pianist – Liszt, Rachmaninoff and Bartók immediately spring to mind, but there are many more examples of first-rate musicians with two or more parallel careers, in a time when the boundaries between disciplines were less defined than now. With increasing specialisation in all areas, it has become much harder to find examples, especially since there is so much more music to know, both for composers and performers. Staying ahead of all the myriad trends in contemporary music is itself more than a full-time occupation for aspiring composers, and the staggering complexity and technical difficulty of much of the instrumental solo repertoire today makes enormous demands on the time, energy and dedication of performers. Not surprisingly, there is often an assumption that one of these activities exist on a lower level of accomplishment than the other – many composers can give somewhat adequate performances of their own works, many performers are able to write unoriginal but conventionally idiomatic solo pieces for their own instrument.

There are many reasons to believe that Miharu Ogura, born 1996 in Tokyo, is the real thing – a supremely accomplished pianist with a boundless appetite for the summits of the contemporary piano repertoire (witness her live recording of Stockhausen’s Klavierstücke I-XI, also on Thanatosis), at the same time a major emerging composer with a growing list of works and a strong and distinctive voice. A casual look at Ogura’s scores suggests some general influences from Ligeti and Dutilleux, later perhaps Boulez and Stockhausen, but it is remarkable how quickly such a young composer has assimilated the musical languages of the entire 20th century and made them her own.

It might seem surprising that Ogura’s first compositions involving the piano were not for solo piano: Réflexion géométrique (2016-17, piano and percussion), Qui bouge dans la nuit? (2017, piano and electronics), Feu improvisé (2017, piano and small orchestra) and Kan (2017-18, three pianos). Such an oblique approach to writing for her own instrument suggests a strong wariness of falling into the trap of the composing performer, and a refusal to take the easy or relaxed paths; indeed, Ogura often talks about the dangers: “My hands know more about the instrument than my head. As long as I compose only by listening to what my hands want, there is a danger that I will only come up with piano writing that I have experienced myself.” Also, about the piece for piano and electronics: ”I used the instrument and my hands while composing, and I realised it’s very hard and dangerous”. Presumably hard to avoid clichés, since it would not be too hard to find any number of composers who find composing at the piano very easy and comfortable indeed.

A remarkable feature of Ogura’s piano writing is that it almost never seems to be conceived for two hands, doing their thing, dependently or independently in different regions of the keyboard, as in most classical and (even) contemporary piano music. Instead, among the large variety of different texture types, there are usually three or four (sometimes even five) different layers of music, moving at different

speeds, often also using different types of rhythmical notation (measured versus free/spaced notation). At other times, both hands are locked into playing complex polyphony in the exact same space, one on top of the other, as in the opening of Labyrinthe. This is obviously a deliberate strategy, of creating a physical sensation that the performer has never experienced before. At the same time, Ogura doesn’t want to neglect the greatest strength of the instrument or herself as a performer – the quality of the instrumental sound itself. Hence, there are no extended playing techniques – everything takes place on the keyboard, meticulously notated, with great attention paid to dynamics, articulation, sonority and resonances – or theatrical elements (although parts of Labyrinthe do involve a visual element in performance).

The earliest piece on this album, Labyrinthe, was written in 2018 for the Orléans International Piano Competition, the only major piano competition wholly dedicated to the music of the 20th and 21st centuries. Every candidate is required to present and premiere a newly written piece by a young composer; not surprisingly, Ogura chose to write a piece for herself, and was duly rewarded not only with the prize for the best composition, but also with a place in the finals. Quite appropriate for a competition piece designed to show off both the performer and the composer, Labyrinthe takes its physical virtuosity to an almost conceptual level, with its deliciously inventive textures, often requiring absurd amounts of hand-crossing. The starting point is a ten-note ostinato figure, harmonically fairly conventional, with a strong octatonic flavour and prominent tritones, that provides the material for the entire piece. It then proceeds through a series of variations, first superimposing fragments of the ostinato at varying speeds into a dense polyrhythmic texture, later branching out into an elegant texture of three rhythmically independent lines, very difficult to play with only two hands. After a brief section where both hands are restricted to a narrow area in the treble, a sudden drop to the extreme bass register takes us to a kind of recapitulation, or rather restatement. Here we encounter the most outrageous texture of all, where both hands are confined to the extreme bass, taking turns leaping to the middle of the keyboard. The video from the premiere at Orléans gives some idea of the sheer physicality of this section, something which can unfortunately only be imagined in an audio recording. This section is mirrored by the next, where both hands are playing repeated notes on the top B flat, making wild leaps in the other direction. A lyrical interlude leads to a rather Nancarrowian three-part canon in three different speeds, spanning the whole keyboard, to be played by one hand only, while the other is occupied with a version of the ostinato, before an explosive coda brings the piece to an end. ”When I composed Labyrinthe, I kind of believed that one can create something new when one writes things which need a new physicality.” The result is an exhilarating and labyrinthine journey through various sound spaces, textures and ways of playing the piano that nobody has ever experienced before.

The short Pas (2019) was intended as a prelude to Labyrinthe. The French title carries a double meaning, suggesting that every gesture in this short, sparse piece is like a step leading into the labyrinth, however, at the same time it is, in its linearity and reflectiveness, the complete negation of Labyrinthe. This ambivalence is also reflected in the musical material, where the pitches are related to Labyrinthe, sometimes obviously so, but the gestures are completely independent. The piece is notated in an unusual way – containing mostly isolated gestures and their resonances, it uses two systems of dynamic markings, one for the actual playing, one for following the decay of

the resonances. On a conceptual level, the piece may be said to be about the attitude of the performer – and, by extension, the listener – to become absorbed in following the resonances of the instrument and the room, almost more so than the actual playing on the keys. ”What I focused on in this piece is to experiment with ways how one can pile sounds up and make them go away. Through these processes we find a material for Labyrinthe.”

Another piece composed for a specific recital occasion, …zwischen… (2020), was intended as a connection piece for the pairing of Johann Sebastian Bach’s D major Partita and Heinz Holliger’s Partita, as a modern-day equivalent of the habit of certain “Golden Age” pianists of improvising transitions between different items on a recital programme (although pianists of that time never had to handle transitions from Bach to Holliger). The improvisatory sound world contrasts effectively with the much

more specifically structured Bach and Holliger. The piece begins with a rather D major-flavoured arpeggio and ends with a very soft, low cluster, otherwise the connections to the surrounding Partitas are limited to referencing common Baroque improvisation patterns – arpeggios, runs, recitatives – that are mostly absent in the Bach Partita, but are extensively used in the Holliger.

The second virtuoso competition show-piece on this album, again for the Orléans competition, again winning the composition prize, Sillage de lignes (2022) was written for and premiered by Ogura’s younger colleague Chisato Taniguchi. The title is a perfume metaphor, referring to the lingering resonances of the slow-moving line in the middle register, held with the sostenuto pedal, that plays a prominent role throughout the piece. Compared to Labyrinthe, the harmonic language is much more chromatic; especially the middle line is mostly concerned with building up small chromatic clusters and slowly letting them evaporate, hinting at the blurred sound world of Nijimi. The textures are less extravagant, but no less sophisticated – more importantly, every section is given more time to develop, in contrast to the kaleidoscopic rush of Labyrinthe.

The first of the four main sections contrasts the Ligetian activity of the outer voices with the aforementioned “lingering” middle voice, perhaps a 21st century version of Schumann’s Innere Stimme, of stillness coexisting with hectic busyness. The fast music soon exhausts itself and descends into the extreme bass for an extended section, before the return of the Innere Stimme. This time it is surrounded by a pointillistic texture, plus an additional layer of very rapid figurations in the highest register, generously tailored to Taniguchi’s virtuosity. After building to a big climax, followed by a transition based around repeated E flats, the last section is unique in Ogura’s piano music for being essentially a rather simple two-part contrapuntal texture – although both hands are extremely busy here, and stretched to their limits with long passages of parallel ninths and sevenths. The last surprise is a slow and reflective coda, with chords slowly descending into darkness.

The largest and most recent work on this recording, Nijimi

(2023), did not originate with a specific occasion – in a

way it was written for this album, but also, and more

importantly, as an exercise in creating larger forms,

considering how rare it is for young composers to receive

commissions for large-scale works. The opening comes

from a short piece composed in 2020 for the birthday of

Ogura’s composition teacher – realising its potential for

development, Ogura used it as a nucleus for a

composition by spontaneous association, growing

organically from simple ideas. The finished piece falls

roughly into four large sections and a coda, but transitions are blurred and spread out by an extensive web of motivic and textural connections. The Japanese verb nijimu (滲む) translates roughly as blur, spread, show through, or generally the behaviour of liquids not being confined within clear boundaries, hence the title refers both to the general approach to form and to the patterns of repeated chords which create an impression of unclear or undefined pitches, something which would seem impossible on the instrument. Another inspiration for the form of the piece comes from Akira Miyoshi’s solo piano masterwork Chaînes, where sections are connected like links in a chain.

The first section uses material rather similar to the slow-moving middle voice of Sillage de lignes, expanded into a complex, multi-layered texture, while the second, more lively and pointillistic section at times recalls Messiaen’s Catalogue d’oiseaux. Given the abundant connections, a description like this can only scratch the surface of a dense web of relations between different elements of the piece. Chordal nijimis start seriously infiltrating the textures towards the end of the second section, and dominate the third, culminating in a series of ever-shifting clusters in the extreme bass. The fourth section introduces a rare tonal element in Ogura’s music, in the form of extremely soft, chorale-like progressions of (mostly) simple triads, though this music is always in danger of being blurred, distorted or simply covered by the atonal music surrounding it. The coda re-harmonises the chorale material in the manner of late Ligeti, now falling instead of rising, before dissolving into the extreme high register.

Nijimi is a remarkable work, of a seriousness and expansiveness that is unusual among recent works for solo piano, with textures that are as delightful as anything in Labyrinthe or Sillage. To this writer at least, Nijimi feels like a spiritual sibling to Helmut Lachenmann’s Serynade – it manages to be both deeply serious and playful, often at the same time, while showing interestingly similar ways of transitioning between very different materials. We have many reasons to look forward to the next big piano work from Ogura.

Thanatosis produktion is a Stockholm-based record label and concert & festival-organization founded in 2016 and operated by Alex Zethson. For full album catalogue see thanatosis.org or thanatosis.bandcamp.com. Also, pay a visit to monopiano.com, the website of MONOPIANO, festival produced by Thanatosis, devoted to piano- and keyboard based music.